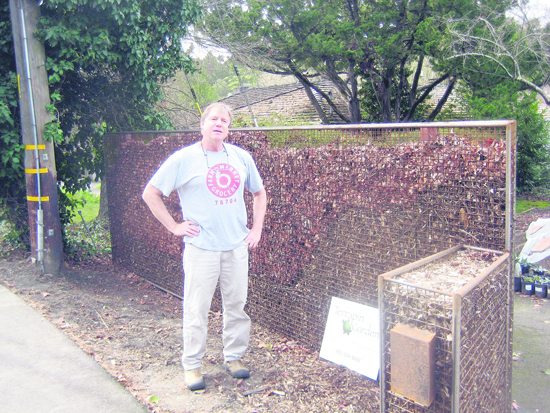

| | | Fred Strauss with his compost fence Photo Sophie Braccini

| | | | | |

When Fred Strauss moved from Austin to Orinda last year, he arrived with years of landscaping experience and an adventurous spirit. Driving past his residence on Glorietta Boulevard, it's hard to miss the metal structure full of mulch and leaves that shields portions of his front yard. At first glance it appears to be a composting fence - a passive composting technique. But to Strauss, the structure is a vegetation version of the gabion walls he built in Texas.

"Four months ago a woman driving down Glorietta in the afternoon fell asleep at the wheel and crashed in the bushes in front of the house," recounts Strauss, "I looked for an idea to replace the dead vegetation and came up with the fence, which is a derivation of the gabions I built in Austin." Strauss thought that some plants, such as epiphytes, would take root in the mulch-and-leaf fence; the rate of decomposition would be very slow since the fence contains only brown material.

"Four months ago a woman driving down Glorietta in the afternoon fell asleep at the wheel and crashed in the bushes in front of the house," recounts Strauss, "I looked for an idea to replace the dead vegetation and came up with the fence, which is a derivation of the gabions I built in Austin." Strauss thought that some plants, such as epiphytes, would take root in the mulch-and-leaf fence; the rate of decomposition would be very slow since the fence contains only brown material.

According to the Seattle Times, "A composting fence attracts wrens and chickadees, and cuts down on the amount of woody waste that must be hauled off because most pruned branches can be cut to fit into the fence. Over time the green waste breaks down to feed the plants growing around it." Strauss loves the way the light shines through the leaves in the morning sun and the different shades of brown that are created as the light changes.

According to the Seattle Times, "A composting fence attracts wrens and chickadees, and cuts down on the amount of woody waste that must be hauled off because most pruned branches can be cut to fit into the fence. Over time the green waste breaks down to feed the plants growing around it." Strauss loves the way the light shines through the leaves in the morning sun and the different shades of brown that are created as the light changes.

There's nothing to stop Strauss from calling his fence a gabion, from the Italian gabbione meaning "big cage," - what counts is the cage that encloses the material. "If you look at what's done in the little artsy town of Marfa in Texas, you see very creative ways these walls have been used in public and private spaces," he says. "I've used it for adding an interesting element of decor in my clients' gardens." Strauss adds that gabion walls or fences can be filled with anything - mulch, wood chips, rock, seashells, leaves, even hay bales. The material used as fill must be larger than the openings in the mesh or welded wire panels; gabions may be fat, thin, tall, short, and may start and stop, turn corners, or curve any way desired. "All you need is a good steel man with welding skills and an artsy spirit," he says. There's nothing to stop Strauss from calling his fence a gabion, from the Italian gabbione meaning "big cage," - what counts is the cage that encloses the material. "If you look at what's done in the little artsy town of Marfa in Texas, you see very creative ways these walls have been used in public and private spaces," he says. "I've used it for adding an interesting element of decor in my clients' gardens." Strauss adds that gabion walls or fences can be filled with anything - mulch, wood chips, rock, seashells, leaves, even hay bales. The material used as fill must be larger than the openings in the mesh or welded wire panels; gabions may be fat, thin, tall, short, and may start and stop, turn corners, or curve any way desired. "All you need is a good steel man with welding skills and an artsy spirit," he says.

One of Strauss's characteristics is to take advantage of a yard's natural circumstance to create something unexpected. "My job is imagining and creating beautiful gardens, with whatever resources might be available," he says. "I can imagine quite a lot, very quickly, and I make a living out of doing that for people." Strauss believes that there is no limit to what people can create between their shelter and the rest of the world if they are free-thinking and willing to garden the way no one has gardened before. "Garden life is never so good as when recycling and recreating bold integration of the natural environment and human-built elements of home," he says.

One of Strauss's characteristics is to take advantage of a yard's natural circumstance to create something unexpected. "My job is imagining and creating beautiful gardens, with whatever resources might be available," he says. "I can imagine quite a lot, very quickly, and I make a living out of doing that for people." Strauss believes that there is no limit to what people can create between their shelter and the rest of the world if they are free-thinking and willing to garden the way no one has gardened before. "Garden life is never so good as when recycling and recreating bold integration of the natural environment and human-built elements of home," he says.

Strauss' landscaping business is called Terrapin Garden; he can be reached at 254-8343.

Strauss' landscaping business is called Terrapin Garden; he can be reached at 254-8343.

|