Broken bones. Double doses of blood pressure pills administered by homecare workers. A neighbor calling long distance about odd bruises she spotted on grandpa's arms. An aunt suffering from poorly managed pain. Grandparents telling Meals on Wheels to hit the road - and not come back. As the senior population increases, providing proper care - especially long distance - can become more complicated.

In 2010, seniors made up 13 percent of America's population, having grown "from 3 million in 1900 to 39 million in 2008," according to "Older Americans: Key Indicators of Well-Being," a report from The Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics.

In 2010, seniors made up 13 percent of America's population, having grown "from 3 million in 1900 to 39 million in 2008," according to "Older Americans: Key Indicators of Well-Being," a report from The Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics.

By 2030, baby Boomers are expected to make that number rise even more dramatically "to 72 million ... representing nearly 20 percent of the total U.S. population."

By 2030, baby Boomers are expected to make that number rise even more dramatically "to 72 million ... representing nearly 20 percent of the total U.S. population."

As a result, more 40- and 50-something children of teachers, scientists, business leaders, and even healthcare professionals are exploring unfamiliar territory - the "parenting" of parents and other relatives.

As a result, more 40- and 50-something children of teachers, scientists, business leaders, and even healthcare professionals are exploring unfamiliar territory - the "parenting" of parents and other relatives.

How are Bay Area residents addressing the needs of their aging relatives? One method many Orindans have employed for years is the in-law apartment. Having Nana and Pop-Pop in a small cottage nearby provides peace of mind and often willing babysitters for occasional nights out while still ensuring that parents or grandparents retain their privacy. Another is to relocate parents to nearby senior housing programs or retirement communities, such as the Orinda Senior Village or Chateau Lafayette.

How are Bay Area residents addressing the needs of their aging relatives? One method many Orindans have employed for years is the in-law apartment. Having Nana and Pop-Pop in a small cottage nearby provides peace of mind and often willing babysitters for occasional nights out while still ensuring that parents or grandparents retain their privacy. Another is to relocate parents to nearby senior housing programs or retirement communities, such as the Orinda Senior Village or Chateau Lafayette.

But what do adult children do when aging parents insist on staying at home - too far across the region or country to be reached quickly?

But what do adult children do when aging parents insist on staying at home - too far across the region or country to be reached quickly?

"If you live an hour or more away from a person who needs care, you can think of yourself as a long-distance caregiver," according to "So Far Away: Twenty Questions and Answers About Long-Distance Caregiving," a publication of the National Institute on Aging.

"If you live an hour or more away from a person who needs care, you can think of yourself as a long-distance caregiver," according to "So Far Away: Twenty Questions and Answers About Long-Distance Caregiving," a publication of the National Institute on Aging.

Activities may involve "arranging for professional caregivers, hiring home health and nursing aides, or locating care in an assisted living facility or nursing home. . . . Some long-distance caregivers find they can be helpful by researching health problems or medicines, paying bills, or keeping family and friends updated" online.

Activities may involve "arranging for professional caregivers, hiring home health and nursing aides, or locating care in an assisted living facility or nursing home. . . . Some long-distance caregivers find they can be helpful by researching health problems or medicines, paying bills, or keeping family and friends updated" online.

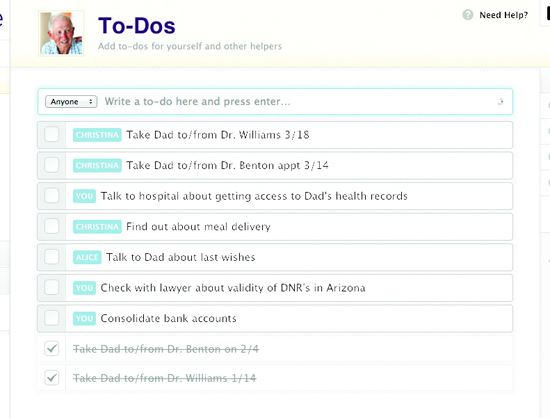

One way they are doing this is through San Francisco-based CareZone, co-founded in 2011 by Jonathan Schwartz, former CEO of Sun Microsystems. "Neither my brother nor I had a safe place to organize information about our families, store important documents or instructions, or a secure way to keep our extended families or helpers up to date. So, like everyone else, we reverted to paper files, phone trees, and lots of email," explains Schwartz. Because there were no web-based tools available to adequately meet caregivers' needs, he left his high tech career to develop a system that would.

One way they are doing this is through San Francisco-based CareZone, co-founded in 2011 by Jonathan Schwartz, former CEO of Sun Microsystems. "Neither my brother nor I had a safe place to organize information about our families, store important documents or instructions, or a secure way to keep our extended families or helpers up to date. So, like everyone else, we reverted to paper files, phone trees, and lots of email," explains Schwartz. Because there were no web-based tools available to adequately meet caregivers' needs, he left his high tech career to develop a system that would.

CareZone serves as an online hub for nurses, therapists, family, and neighbors to "manage, coordinate and archive private family information in a single, secure place." The system's Profile and Contacts tools allow users to enter blood types, allergies and other important data for loved ones, as well as contact information for support staff including physicians, homecare workers, and clergy, while the Journal function helps users to share private diaries to document daily living, the progress being made with treatment, and other issues. The fee is $48 per year for the person receiving care; access may then be shared by the registered member with as many people as needed without additional fees.

CareZone serves as an online hub for nurses, therapists, family, and neighbors to "manage, coordinate and archive private family information in a single, secure place." The system's Profile and Contacts tools allow users to enter blood types, allergies and other important data for loved ones, as well as contact information for support staff including physicians, homecare workers, and clergy, while the Journal function helps users to share private diaries to document daily living, the progress being made with treatment, and other issues. The fee is $48 per year for the person receiving care; access may then be shared by the registered member with as many people as needed without additional fees.

The Institute on Aging also recommends scheduling family meetings - before any emergency - to discuss what family members want as they age. Do they hope to remain in their New England homes, or would they prefer to become "snowbirds" and head for California?

The Institute on Aging also recommends scheduling family meetings - before any emergency - to discuss what family members want as they age. Do they hope to remain in their New England homes, or would they prefer to become "snowbirds" and head for California?

What types of medical interventions do they want and for how long? Have they written advance directives and, if so, did they address how they want their pain managed and whether or not they want to be placed on ventilators, or fed through tubes if the worst happens? What kind of spiritual care do they want - if any? Will their physicians and nurses accommodate those requests?

What types of medical interventions do they want and for how long? Have they written advance directives and, if so, did they address how they want their pain managed and whether or not they want to be placed on ventilators, or fed through tubes if the worst happens? What kind of spiritual care do they want - if any? Will their physicians and nurses accommodate those requests?

Molly Jones, administrator of the Rheem Valley Convalescent Hospital, often counsels adults thrown into crisis by their parents' unexpected medical problems and agrees that starting a dialogue early is crucial. Some parents may not have much money, but may have great insurance; others may have savings that will be quickly depleted because their insurance covers extended care in a skilled nursing facility, but not out-patient care - or vice versa.

Molly Jones, administrator of the Rheem Valley Convalescent Hospital, often counsels adults thrown into crisis by their parents' unexpected medical problems and agrees that starting a dialogue early is crucial. Some parents may not have much money, but may have great insurance; others may have savings that will be quickly depleted because their insurance covers extended care in a skilled nursing facility, but not out-patient care - or vice versa.

And while the goal is to help parents remain in their communities as long as possible, children need to become educated about the nuts and bolts of their parents lives in order to become effective advocates for them when help is required. Jones notes that this is particularly important whenever a loved one is diagnosed with a debilitating condition such as Parkinson's Disease, and advises families to come together to develop plans to estimate what their lives will look like in two years, five, and beyond.

And while the goal is to help parents remain in their communities as long as possible, children need to become educated about the nuts and bolts of their parents lives in order to become effective advocates for them when help is required. Jones notes that this is particularly important whenever a loved one is diagnosed with a debilitating condition such as Parkinson's Disease, and advises families to come together to develop plans to estimate what their lives will look like in two years, five, and beyond.

"The goal," says Jones, "is to really have quality time."

"The goal," says Jones, "is to really have quality time."

|