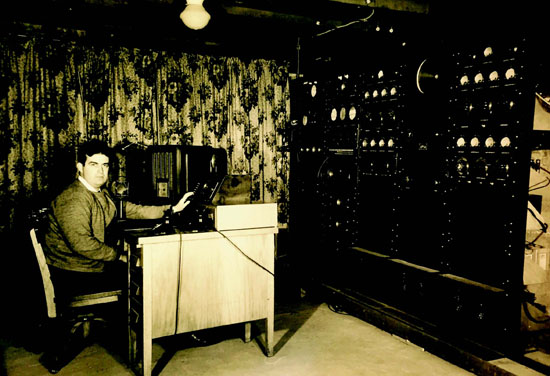

| | | Reginald Tibbetts, in 1942 with his electronic gear. Original photo by Clyde H. Sunderland, Oakland. (This photo also appears on page 84 of the book "Images of America: Port Chicago" by Dean L. McLeod and page 92 of "Images of America: San Francisco in WW II" by John Garvey.) Photos courtesy Moraga Historical Society | | | | | | A 76-year-old home sits on the outskirts of Moraga. Grape leaves blossom in its vineyard and the landscaped grounds are a visual treat, but equally important is what is missing.

Gone today is the radio tower used by its original owner. Gone is the underground gasoline tank, the World War II victory garden and the blackout curtains over its windows. Gone is the office and shop housing engineering research and development important to the Allied cause. Gone, too, is an Eagle Scout and Orinda Scoutmaster, amateur radio operator, UC Berkeley electrical engineering graduate, third generation Californian, 57-year Moraga resident, father, former postmaster - all one and the same man - the reclusive D. Reginald Tibbetts.

Gone today is the radio tower used by its original owner. Gone is the underground gasoline tank, the World War II victory garden and the blackout curtains over its windows. Gone is the office and shop housing engineering research and development important to the Allied cause. Gone, too, is an Eagle Scout and Orinda Scoutmaster, amateur radio operator, UC Berkeley electrical engineering graduate, third generation Californian, 57-year Moraga resident, father, former postmaster - all one and the same man - the reclusive D. Reginald Tibbetts.

Elsie Mastick called Tibbetts "our Moraga spy." Mastick, a Moraga Historical Society member, was friends with Tibbetts' daughter. "He broke the code," Mastic said proudly of Tibbetts' work intercepting and deciphering Japanese transcripts as the two countries moved toward war.

Elsie Mastick called Tibbetts "our Moraga spy." Mastick, a Moraga Historical Society member, was friends with Tibbetts' daughter. "He broke the code," Mastic said proudly of Tibbetts' work intercepting and deciphering Japanese transcripts as the two countries moved toward war.

Records show that Tibbetts purchased an 8-acre parcel in Moraga in 1936 and had built his house by 1939. A licensed amateur radio operator, call sign W6ITH, Tibbetts also built a radio tower on site. "It was magnificent," John LaRue of RedStone Products said admiringly of the "very first class" high frequency radio gear and large log periodic satellite antenna Tibbetts had assembled on site. LaRue, who visited the Moraga acreage, said Tibbetts was one of the first to own a large residential receive-only microwave dish.

Records show that Tibbetts purchased an 8-acre parcel in Moraga in 1936 and had built his house by 1939. A licensed amateur radio operator, call sign W6ITH, Tibbetts also built a radio tower on site. "It was magnificent," John LaRue of RedStone Products said admiringly of the "very first class" high frequency radio gear and large log periodic satellite antenna Tibbetts had assembled on site. LaRue, who visited the Moraga acreage, said Tibbetts was one of the first to own a large residential receive-only microwave dish.

At the time, the Federal Communications Commission required satellite dishes to be licensed. Barbara Tibbetts Workinger became an amateur radio operator at her father's urging, but she has since let her license lapse. Although she remembers a family victory garden filled with tomatoes, it is unclear whether as a child Workinger understood the importance of her father's work. She did remember "all these famous men" her father knew, including Glenn Seaborg (Atomic Energy Commission chairman throughout the 1960s) and her godfather Ernest Lawrence lounging around her family's pool.

At the time, the Federal Communications Commission required satellite dishes to be licensed. Barbara Tibbetts Workinger became an amateur radio operator at her father's urging, but she has since let her license lapse. Although she remembers a family victory garden filled with tomatoes, it is unclear whether as a child Workinger understood the importance of her father's work. She did remember "all these famous men" her father knew, including Glenn Seaborg (Atomic Energy Commission chairman throughout the 1960s) and her godfather Ernest Lawrence lounging around her family's pool.

It was no mere coincidence that Tibbetts was appointed postmaster of Moraga during World War II. It was a move that facilitated the clandestine shipment of equipment he needed to complete his war work - part of which was the development of a Geiger counter used in the early development of the atomic bomb.

It was no mere coincidence that Tibbetts was appointed postmaster of Moraga during World War II. It was a move that facilitated the clandestine shipment of equipment he needed to complete his war work - part of which was the development of a Geiger counter used in the early development of the atomic bomb.

Tibbetts was just plain "Reggie" to Ernest Lawrence, said his son Robert Lawrence, MD. The younger Lawrence remembers visiting Tibbetts' Moraga home with his father "several times a year" as a teen in the mid-1950s. Father and son saw the Tibbetts' radio room filled with shortwave radio equipment and clocks set for time zones around the world.

Tibbetts was just plain "Reggie" to Ernest Lawrence, said his son Robert Lawrence, MD. The younger Lawrence remembers visiting Tibbetts' Moraga home with his father "several times a year" as a teen in the mid-1950s. Father and son saw the Tibbetts' radio room filled with shortwave radio equipment and clocks set for time zones around the world.

Ernest Lawrence was "a big radio nut," his son explained, having built an entire station while attending the University of South Dakota. "We'd go out several times a year [to Moraga]," the younger Lawrence said. He thought Tibbetts was "very rich," based on the "neat things and toys" around the home, including Lawrence's favorite, a motorized electric jeep Tibbetts built for kids. Ernest Lawrence even listened in on an August 1945 shortwave radio communication Tibbetts held with an amateur radio operator in Japan. The resulting nuclear electromagnetic pulse cut off their communications at the precise moment the bomb went off.

Ernest Lawrence was "a big radio nut," his son explained, having built an entire station while attending the University of South Dakota. "We'd go out several times a year [to Moraga]," the younger Lawrence said. He thought Tibbetts was "very rich," based on the "neat things and toys" around the home, including Lawrence's favorite, a motorized electric jeep Tibbetts built for kids. Ernest Lawrence even listened in on an August 1945 shortwave radio communication Tibbetts held with an amateur radio operator in Japan. The resulting nuclear electromagnetic pulse cut off their communications at the precise moment the bomb went off.

"He [Tibbetts] looked at his watch," Robert Lawrence said, "and marked the time."

"He [Tibbetts] looked at his watch," Robert Lawrence said, "and marked the time."

Moraga resident Steve Mazaika, whose grandmother lived near the Tibbetts home, said, "I was kinda scared of the guy" growing up. Tibbetts "wasn't that friendly," Mazaika said. But when it came to electronics and phones, he was very knowledgeable, and had the ability to "call around the world [toll free]" at a time when it was rather costly to do so. Communications from the South Pacific during World War II went through him directly to the Pentagon, Mazaika said.

Moraga resident Steve Mazaika, whose grandmother lived near the Tibbetts home, said, "I was kinda scared of the guy" growing up. Tibbetts "wasn't that friendly," Mazaika said. But when it came to electronics and phones, he was very knowledgeable, and had the ability to "call around the world [toll free]" at a time when it was rather costly to do so. Communications from the South Pacific during World War II went through him directly to the Pentagon, Mazaika said.

A Moraga firefighter for 38 years, Mazaika was sent on medical calls to Tibbetts' home before he died in Moraga on Nov. 24, 1996. Tibbetts was 85.

A Moraga firefighter for 38 years, Mazaika was sent on medical calls to Tibbetts' home before he died in Moraga on Nov. 24, 1996. Tibbetts was 85.

|