|

|

|

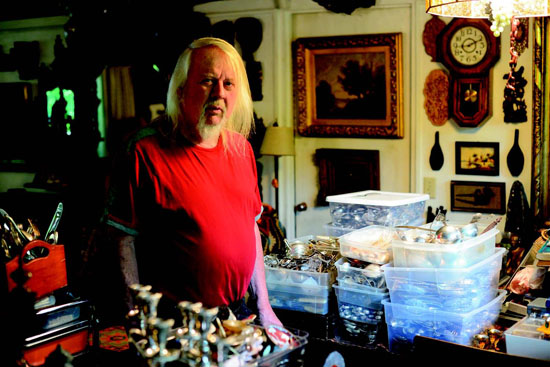

Richard Knapp Photo Ohlen Alexander

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you have visited the Alameda Point Antiques and Collectibles Show or any of the local street festivals or peddler's fairs over the years, you have probably noticed a distinctive man with long silver locks, surrounded by display cases filled with glittering silver flatware and other silver items, and sporting a vest draped with miniature spoons and medals. That would be Lamorindan Richard Knapp, a specialist in his field of antique flatware sales, but also a craftsman, show promoter, world traveler, art dealer and antiques collector with a range reflecting his profound knowledge of history and geography.

Born and raised in Martinez, Knapp has lived in Lamorinda since 1979. His father, a Dutch immigrant, worked for Royal Dutch Shell, first in Rotterdam, then the West Indies, and finally in Martinez. Knapp honors his Dutch roots, and punctuates his antique show wardrobe with a jaunty Dutch cap. His son, fittingly named Jan (pronounced "Yahn"), is a product of Lamorinda schools and lives nearby.

Born and raised in Martinez, Knapp has lived in Lamorinda since 1979. His father, a Dutch immigrant, worked for Royal Dutch Shell, first in Rotterdam, then the West Indies, and finally in Martinez. Knapp honors his Dutch roots, and punctuates his antique show wardrobe with a jaunty Dutch cap. His son, fittingly named Jan (pronounced "Yahn"), is a product of Lamorinda schools and lives nearby.

An early '60s graduate of San Francisco State College (now University), Knapp was headed for a management career in the retail field after college. He worked for a year after graduation as a junior executive for The Emporium, San Francisco's premier department store, and then took his first vacation, "glad to get out of that consciousness.

An early '60s graduate of San Francisco State College (now University), Knapp was headed for a management career in the retail field after college. He worked for a year after graduation as a junior executive for The Emporium, San Francisco's premier department store, and then took his first vacation, "glad to get out of that consciousness.

"l sent a telegram from Tokyo telling them that vacation was taking a little longer than planned," he says wryly. Then he started traveling around the world. He has covered 85 countries to date, usually in pursuit of his work.

"l sent a telegram from Tokyo telling them that vacation was taking a little longer than planned," he says wryly. Then he started traveling around the world. He has covered 85 countries to date, usually in pursuit of his work.

How did he become a retailer of all manner of objects? "A collector who runs out of space at home becomes a retailer," he explains. At the time he took his extended vacation, he was living at home. He had planned to buy a Samurai sword for his bedroom, and he indeed bought one in Japan - and then bought a Chinese sword, and others as he worked his way east. By the time he returned home, he had 35 swords.

How did he become a retailer of all manner of objects? "A collector who runs out of space at home becomes a retailer," he explains. At the time he took his extended vacation, he was living at home. He had planned to buy a Samurai sword for his bedroom, and he indeed bought one in Japan - and then bought a Chinese sword, and others as he worked his way east. By the time he returned home, he had 35 swords.

"My mother told me I could keep one and had to get rid of the rest," he says. It took him six months to sell them off, and a career was born. He travels throughout the world picking up items that interest him, and although he particularly favors Asian art, his tastes are definitely eclectic. His house is filled with oil paintings, antiquities, and objects d'art of all sorts, each with a fascinating story. Among them, for example, is a series of prints by Wendy Yoshimura, one of the Symbionese Army abductors of Patty Hearst - as well as an oil painting by a renowned Dutch master.

"My mother told me I could keep one and had to get rid of the rest," he says. It took him six months to sell them off, and a career was born. He travels throughout the world picking up items that interest him, and although he particularly favors Asian art, his tastes are definitely eclectic. His house is filled with oil paintings, antiquities, and objects d'art of all sorts, each with a fascinating story. Among them, for example, is a series of prints by Wendy Yoshimura, one of the Symbionese Army abductors of Patty Hearst - as well as an oil painting by a renowned Dutch master.

Although he has slowed down a bit due to health issues, he still goes out on a treasure hunt when he can. "Six of us travel together, including an architect, a landscape designer, and so forth," he says. "We go over to a country, rent a 40-foot container, and fill it." Then they return to sell off their prizes - although some end up, at least for a while, in or around Knapp's shady, secluded home. A few years ago he and his group chartered a boat and cruised the Mekong River in Thailand, Laos and Vietnam. "We filled it," he says succinctly, pointing out two large stone Buddhas in his lush garden. On a more recent trip, he and his group traveled throughout Estonia, Finland and Russia filling their collective shopping cart. He sells much of his Asian art to a firm in San Francisco's design district, as well as to architectural designers. A temple door with its original frame that he imported graces the Standard Oil office building in Los Angeles.

Although he has slowed down a bit due to health issues, he still goes out on a treasure hunt when he can. "Six of us travel together, including an architect, a landscape designer, and so forth," he says. "We go over to a country, rent a 40-foot container, and fill it." Then they return to sell off their prizes - although some end up, at least for a while, in or around Knapp's shady, secluded home. A few years ago he and his group chartered a boat and cruised the Mekong River in Thailand, Laos and Vietnam. "We filled it," he says succinctly, pointing out two large stone Buddhas in his lush garden. On a more recent trip, he and his group traveled throughout Estonia, Finland and Russia filling their collective shopping cart. He sells much of his Asian art to a firm in San Francisco's design district, as well as to architectural designers. A temple door with its original frame that he imported graces the Standard Oil office building in Los Angeles.

Knapp is also a promoter in his own right. For 10 years he ran the annual Shadelands antique show at Shadelands Ranch in Walnut Creek, a fundraiser for the Walnut Creek Historical Society that is held under the towering oak trees around the old farmhouse. "He knew all the ins and outs and knew all the dealers," says Martinez resident Steve Martindell, who learned the ropes from Knapp and took over the show for two years after Knapp decided to move on.

Knapp is also a promoter in his own right. For 10 years he ran the annual Shadelands antique show at Shadelands Ranch in Walnut Creek, a fundraiser for the Walnut Creek Historical Society that is held under the towering oak trees around the old farmhouse. "He knew all the ins and outs and knew all the dealers," says Martinez resident Steve Martindell, who learned the ropes from Knapp and took over the show for two years after Knapp decided to move on.

So how did Knapp become Lamorinda's silverware maven? Back in the early '90s, he was selling ethnic art at a Marin flea market, and had a few pieces of sterling silver on his table. "A guy with a footlocker came up to me and said someone had told him I'd buy anything." Then the man made Knapp an offer for the footlocker, which was filled with his family's silver. Knapp could not refuse. Thinking that the footlocker was a salable item, Knapp accepted the offer. "I sold $200 worth [of the silverware] that day, then the same the following week," he muses, and a business was born.

So how did Knapp become Lamorinda's silverware maven? Back in the early '90s, he was selling ethnic art at a Marin flea market, and had a few pieces of sterling silver on his table. "A guy with a footlocker came up to me and said someone had told him I'd buy anything." Then the man made Knapp an offer for the footlocker, which was filled with his family's silver. Knapp could not refuse. Thinking that the footlocker was a salable item, Knapp accepted the offer. "I sold $200 worth [of the silverware] that day, then the same the following week," he muses, and a business was born.

Over the years he has developed an immense knowledge of silverware patterns, and he can probably replace that teaspoon you misplaced from Aunt Ruth's heirloom silver if you can show him a piece of the same pattern. He also sells flatware to startup and established restaurants, and has about 15 regular restaurant customers to supply.

Over the years he has developed an immense knowledge of silverware patterns, and he can probably replace that teaspoon you misplaced from Aunt Ruth's heirloom silver if you can show him a piece of the same pattern. He also sells flatware to startup and established restaurants, and has about 15 regular restaurant customers to supply.

And what about those miniature replica silverware pins that dangle from Knapp's signature vest? "Between 1900 and the Depression, girls usually got married when they graduated from high school. The local jeweler would bestow these little pins on the girls as graduation gifts," he explains, with a not-so-subtle reminder that the jeweler carried that pattern in his store. The girls wore the pins on their sweaters, a set of the silverware would become a graduation gift (this was before the days of gift registries), and the hopeful bride-to-be would find one of the pins attached inside the case as well.

And what about those miniature replica silverware pins that dangle from Knapp's signature vest? "Between 1900 and the Depression, girls usually got married when they graduated from high school. The local jeweler would bestow these little pins on the girls as graduation gifts," he explains, with a not-so-subtle reminder that the jeweler carried that pattern in his store. The girls wore the pins on their sweaters, a set of the silverware would become a graduation gift (this was before the days of gift registries), and the hopeful bride-to-be would find one of the pins attached inside the case as well.

|