| ||||||

MOFD personnel on site included Emergency Preparedness Coordinator Dennis Rein, Capt. Mike Marquardt and engineers Steve Rogness and Dave Mazaika. The men shared their

experiences as members of the South Central Sierra Interagency Incident Management Team, based in Hayfork, about 45 miles west of Redding in heavily forested Trinity County.

Interagency incident management teams are called together when fires grow too large or complex for local agencies to handle. The teams comprise people who are called up from their regular jobs when an incident requires their specialized services.

The August North Complex fire was managed by the U.S. Forest Service, which put together an incident management team in Hayfork in the middle of the Shasta-Trinity National Forest. Base camp peaked at 500 personnel, with half of the group firefighters, half of the group the incident support system.

"We built a small city within a 48-hour period," Mazaika said.

A typical day began with a 7 a.m. briefing, with most activity wrapped up by 10 p.m.

Marquardt, the Line Safety Officer, worked out in the field as the eyes and ears for incident safety. He verified escape routes. Are firefighters wearing the proper equipment? How are the road conditions? He confirmed weather reports. Weather extremes ranged from the possibility of heatstroke in August to frostbite in November; one morning, the temperature dropped to 12 degrees.

"Firefighters are fighting fires. They aren't looking out for these things," Marquardt said.

When an accident did happen, Mazaika, the medical unit leader, took over. His responsibilities included the supervision of emergency medical technicians, who themselves took care of the firefighters, and the administering of medical care needed by any member of the interagency team.

No serious accidents, and no COVID outbreaks, occurred during Mazaika's assignment. "Just a couple of minor incidents," he said.

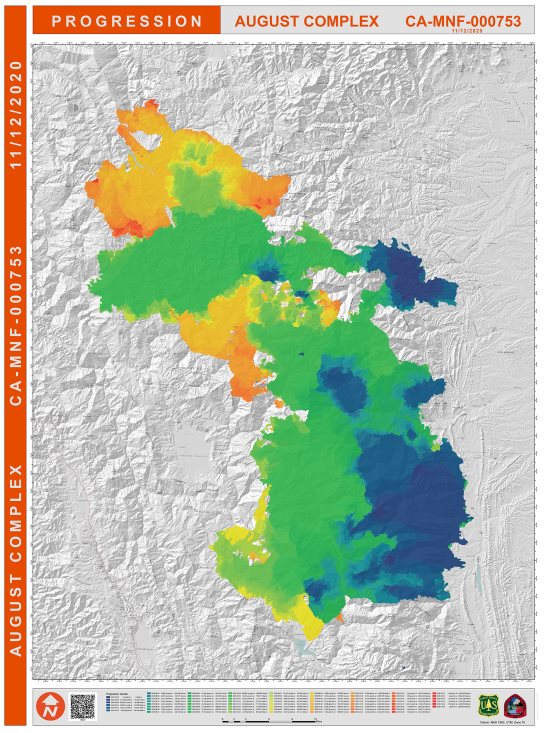

GIS specialist Rogness toiled much of the time in a trailer, creating maps. Operational maps. Aviation maps. Scale maps. Progress maps for media and public officials. More than 20 types of maps.

"Every day, crews would come back with new information and Steve would enter that information into his maps," Marquardt said. Rogness shared a fascinating progression map of the wildfire, showing the fire's origin in August through its peak in late October. (see photo)

Base camp included numerous staff and management personnel. Finance managers kept time sheets, paid suppliers, managed cash flow. The Logistics division obtained food, executed contracts for laundry, cleaning services, portable trailers and toilets. Contractors erected a medical tent and a communications center, and organized accommodations for the 500 personnel. The communications office kept local residents and public officials up to speed.

And that was where Rein, the liaison officer, stepped in. His job was to relay complete, accurate information from the incident command post to outside stakeholders: national forest personnel, the state fire agency, Fish and Game, local police, townspeople and public officials.

Rein recalled a briefing he presented to the Trinity County Board of Supervisors.

"Why did you close Route 36?" the board demanded, as that road is one of the primary thoroughfares through the county.

"It wasn't us," Rein told the board. "It was Caltrans, not the fire organizations." He convinced the supervisors that the closure was ordered for public safety.

Agricultural cannabis is a growth industry in Trinity County, and Rein said the team had no issue with the residents over the product. "But you could tell that the local folks knew exactly where you were," he said.

Once the firefighters contained the August Complex fire, the cleanup phase began.

"It became fire suppression repair," Rein said.

The crews spent days doing erosion control along the bulldozer lines. They knocked down berms. Added water bars. Removed dead trees along Route 36. Along that same highway, more than 7,000 damaged guardrails were replaced.

The goals were to protect the area from mudslides and harsh weather events, and to have the region return to as natural a look as possible.

"Return" was a word that Marquardt could rarely identify with over the summer and fall. He served on four incident teams beginning Aug. 1, from Orange County to the Diablo Range to Trinity County. "Eighty-five days out of the district, home for only nine," Marquardt said.

But not one of the participants even implied that the time spent on the outside teams was not worthwhile.

"Working with the incident management team provides MOFD personnel the opportunity to see large fire operations first hand, as well as share their MOFD expertise with other agencies," Rein said.

The expenses related to the firefighters' work on the incident management team are reimbursed to the district by the federal government.

Reach the reporter at: