|

|

Published June 26th, 2019

|

Working toward recovery

|

|

| By Diane Claytor |

|

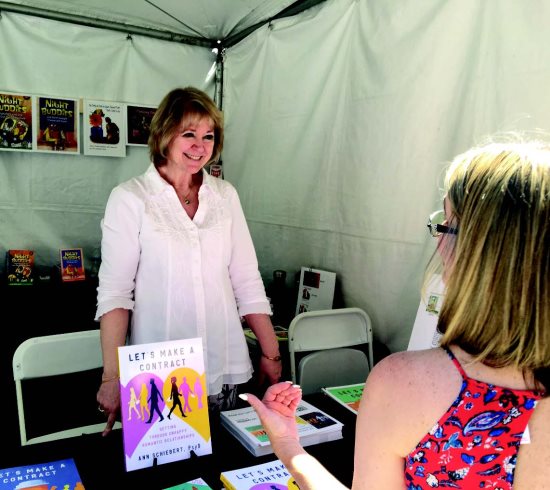

| Psychologist and author Ann Schiebert at a book signing event. Photo provided |

Not many parents would say that watching the arrest of their 17-year-old son was the “best thing that could have happened.” But that’s exactly what Lafayette’s Ann Schiebert recently said, more than 30 years after that drug-related arrest and 11 years after that same son, Michael, died of a methadone overdose.

Of course, those years brought confusion, self-doubt and more heartbreak than any parent should ever have to endure. But because of her son’s addiction and many years of pain, Schiebert dramatically changed her life; she became a highly respected psychologist, working in the mental health clinic of a major national HMO. She treats patients dealing with trauma and chemical dependency and serves as a psychiatric crisis specialist. She also has a private practice specializing in codependency issues. Schiebert’s expertise in this area has also led her to author several well-received books, host a radio talk show and occasionally hit the speaker circuit. Of course, those years brought confusion, self-doubt and more heartbreak than any parent should ever have to endure. But because of her son’s addiction and many years of pain, Schiebert dramatically changed her life; she became a highly respected psychologist, working in the mental health clinic of a major national HMO. She treats patients dealing with trauma and chemical dependency and serves as a psychiatric crisis specialist. She also has a private practice specializing in codependency issues. Schiebert’s expertise in this area has also led her to author several well-received books, host a radio talk show and occasionally hit the speaker circuit.

Raised in the East Bay and a graduate of both Head Royce and Holy Names College, Schiebert married, moved to Orinda, became a top producing realtor in the Lamorinda community, had three children and seemed to be living the suburban dream. Then came a divorce and the discovery that Michael was doing drugs. “When Michael started banging on the car with a hammer and threatening to kill me and my daughter,” Schiebert sadly recalls, “I knew I had to do something.” The police were called and Michael was arrested. “He spent his 18th birthday in juvenile hall. I took him a Big Mac to celebrate,” Schiebert remembers. Raised in the East Bay and a graduate of both Head Royce and Holy Names College, Schiebert married, moved to Orinda, became a top producing realtor in the Lamorinda community, had three children and seemed to be living the suburban dream. Then came a divorce and the discovery that Michael was doing drugs. “When Michael started banging on the car with a hammer and threatening to kill me and my daughter,” Schiebert sadly recalls, “I knew I had to do something.” The police were called and Michael was arrested. “He spent his 18th birthday in juvenile hall. I took him a Big Mac to celebrate,” Schiebert remembers.

“I had no idea what to do,” Schiebert admits. On a court order, Michael entered a residential care treatment facility for teenagers in Oakland and Schiebert attended every family meeting and read every book she could find on the subject of addiction. “I knew things had to change, so I became a really good student, learning everything I could on this topic,” she reports. She even took a job at the treatment facility because “I needed to learn more about this disease and what Michael was going through.” “I had no idea what to do,” Schiebert admits. On a court order, Michael entered a residential care treatment facility for teenagers in Oakland and Schiebert attended every family meeting and read every book she could find on the subject of addiction. “I knew things had to change, so I became a really good student, learning everything I could on this topic,” she reports. She even took a job at the treatment facility because “I needed to learn more about this disease and what Michael was going through.”

Michael came home after 30 days with a contract that stated any relapse would result in his being forced to leave the house. He relapsed and Schiebert followed through. “It was the hardest thing I have ever done in my entire life,” she says. “But he knew in advance the consequences of making that choice. What often looks like cruelty – kicking out, forcing into rehab – is often the most loving thing a parent can do for someone who’s addicted,” Schiebert adds. Michael came home after 30 days with a contract that stated any relapse would result in his being forced to leave the house. He relapsed and Schiebert followed through. “It was the hardest thing I have ever done in my entire life,” she says. “But he knew in advance the consequences of making that choice. What often looks like cruelty – kicking out, forcing into rehab – is often the most loving thing a parent can do for someone who’s addicted,” Schiebert adds.

Eventually Michael got clean and sober, found employment, married and started a family. But then, unfortunately, he had an accident, got hooked on opioids and one morning “just stopped breathing.” Eventually Michael got clean and sober, found employment, married and started a family. But then, unfortunately, he had an accident, got hooked on opioids and one morning “just stopped breathing.”

“As devastated and shocked as I was,” Schiebert says, “I can’t say I was all that surprised because his addiction was so pervasive. There’s nothing we can do for people who don’t want to change, as heartbreaking as that is.” “As devastated and shocked as I was,” Schiebert says, “I can’t say I was all that surprised because his addiction was so pervasive. There’s nothing we can do for people who don’t want to change, as heartbreaking as that is.”

Over those years, Schiebert felt compelled to make drastic changes in her life. She enrolled at JFK University and, while still working as a real estate agent, earned her doctor of psychology degree. She got a job working with addicted teens and quickly came to understand that parents often don’t tell their children exactly what is expected of them or discuss family values or what consequences there may be for disrespecting these values or the house rules. Parents often expect their teens to “simply know” without any real conversation. Over those years, Schiebert felt compelled to make drastic changes in her life. She enrolled at JFK University and, while still working as a real estate agent, earned her doctor of psychology degree. She got a job working with addicted teens and quickly came to understand that parents often don’t tell their children exactly what is expected of them or discuss family values or what consequences there may be for disrespecting these values or the house rules. Parents often expect their teens to “simply know” without any real conversation.

From this realization, Schiebert created a contract that covers a family’s values and expectations, as well as the consequences for ignoring them. “This way,” she explains, “the teen knows, in advance, what is expected and what the repercussions are. Then there’s really no argument because everyone knows what to expect when choices are made.” She tried these contracts out in her practice and it proved to be a very successful program. “I call it PEP-C – preemptive parenting by contract,” Scheibert says. “And it works!” From this realization, Schiebert created a contract that covers a family’s values and expectations, as well as the consequences for ignoring them. “This way,” she explains, “the teen knows, in advance, what is expected and what the repercussions are. Then there’s really no argument because everyone knows what to expect when choices are made.” She tried these contracts out in her practice and it proved to be a very successful program. “I call it PEP-C – preemptive parenting by contract,” Scheibert says. “And it works!”

So she took it a step further and wrote the first in her successful “Lets Make a Contract” series of books, “Getting Your Teen Through High School and Beyond.” So she took it a step further and wrote the first in her successful “Lets Make a Contract” series of books, “Getting Your Teen Through High School and Beyond.”

Schiebert refers to these contracts as “kind and loving.” And it’s not just the kids who are to blame if things go wrong. There are also consequences for the parents if they don’t respect the family’s values, which, according to Schiebert, the teens definitely appreciate. Schiebert refers to these contracts as “kind and loving.” And it’s not just the kids who are to blame if things go wrong. There are also consequences for the parents if they don’t respect the family’s values, which, according to Schiebert, the teens definitely appreciate.

Writing from an experiental perspective, Schiebert’s other “Lets Make a Contract” books include “Getting Your Teen Through Substance Abuse” and, her newest one, “Getting Your Teen Past the Opioid Epidemic.” (Schiebert’s fourth book in the series addresses an issue everyone experiences at one time or another: “Getting Through Unhappy Romantic Relationships.”) Writing from an experiental perspective, Schiebert’s other “Lets Make a Contract” books include “Getting Your Teen Through Substance Abuse” and, her newest one, “Getting Your Teen Past the Opioid Epidemic.” (Schiebert’s fourth book in the series addresses an issue everyone experiences at one time or another: “Getting Through Unhappy Romantic Relationships.”)

To order any of Schiebert’s “Let’s Make a Contract” books, go to

www.drannschiebert.com. To order any of Schiebert’s “Let’s Make a Contract” books, go to

www.drannschiebert.com.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|